Functional Programming in Swift

14th June 2018 • 1,848 words • 12 minutes reading time.

What is Functional Programming and how can we use it in Swift?

Search online for any definition of functional programming and you will find many different definitions, few of which are practically helpful. I have no claim to be an expert, but as a Swift enthusiast, this is what I have distilled out of the morass.

What is Functional Programming?

Without providing a concrete definition, here are what I see as the 3 main goals of functional programming:

- use pure functions where possible

- avoid mutability where possible

- use functions as the basic building blocks

So let's go through those one by one and see how they fit into the Swift language.

Functional Programming in Swift

You can download a playground containing all these examples from GitHub.

Pure functions

A function is considered pure if it will always produce the same result for the same input, regardless of where it is and what calls it.

Imagine you are writing a role-playing game and for a given fight, you need to be able to calculate the damage per second caused by a character.

class DamageDealer {

var damageDone: Int = 0

var timeTaken: TimeInterval = 0

func damagePerSecond() -> Double {

if timeTaken == 0 {

return 0

}

let dps = Double(damageDone) / timeTaken

if dps < 0 {

return 0

}

return dps

}

}

let mage = DamageDealer()

mage.damageDone = 32

mage.timeTaken = 10

mage.damagePerSecond()The damagePerSecond function takes no parameters but uses the properties of its containing object. This works in this class, but there are 3 big problems:

- The function is not transportable - you cannot copy it into another class as it is totally dependent on the structure of the properties in the containing class.

- When calling the function, it is not clear what data it is going to use.

- This function is difficult to test as calling the function with the same parameters (none) will produce different results depending on the setup.

So for a version that uses a pure function, we could replace damagePerSecond() with this:

func damagePerSecondPure(damage: Int, time: TimeInterval) -> Double {

if time == 0 {

return 0

}

let dps = Double(damage) / time

if dps < 0 {

return 0

}

return dps

}

mage.damagePerSecondPure(damage: mage.damageDone, time: mage.timeTaken)Calling the function is now more verbose, but reading the call gives you much more information about what is going to happen. Testing is easy, and the function is completely self-contained so can be copied into any class or struct.

Avoid mutability

This one has become the poster child of Swift Functional Programming as Swift provides some very convenient ways to avoid mutability.

The first is let versus var. My rule is always to start defining any variable/constant with let and only changing to var if the compiler raises an error. In the current versions of Xcode, it will give a warning if you use var unnecessarily which is great, but I still stick to using let first.

The most powerful way Swift lets us avoid mutability with Functional Programming is with map, filter and reduce.

Filter

Consider this function that checks possible player names:

func checkPlayerNames(names: [String]) -> [String] {

var validNames: [String] = []

for name in names {

if name.count > 3 && !name.contains(" ") {

validNames.append(name)

}

}

return validNames

}

let allNames = [ "Woody", "Rex", "Slinky", "Buzz Lightyear", "Hamm" ]

let checkedNames = checkPlayerNames(names: allNames)Only names with more than 3 characters and no spaces are considered valid. So this function creates an empty array and then loops through each member of the supplied array and appends any valid names to the new array before returning it.

This function is a pure function and it works as expected. But the validNames array is mutable and there is no need for it to be.

Converting this to avoid mutability, we get:

func checkPlayerNamesUsingFilter(names: [String]) -> [String] {

let validNames = names.filter { name in

name.count > 3 && !name.contains(" ")

}

return validNames

}Inside the filter closure delimited by the curly braces after the word filter, (more about closures below), the element in the array being evaluated is stored in the name constant. The checks are done and this implicitly returns a Bool - true if the checks pass, false if they do not. If the closure returns true, the name is valid and will be part of the validNames array.

And if you really want to be concise:

func checkPlayerNamesUsingFilterShort(names: [String]) -> [String] {

return names.filter { $0.count > 3 && !$0.contains(" ") }

}I recommend the first method even if it is a bit more verbose. Storing the result in a constant before returning it makes debugging much easier. Using $0 instead of using a named parameter is convenient, but I prefer not to do this unless the closure is very simple.

Map

filter takes an array of objects and returns a sub-array containing every element which returned true for the checks inside the filter body.

map changes the elements in an array and can return an array of the same type or an array of different types.

Here is a function to square every integer in an array in the old style, using a mutable array to accumulate the result:

func squareNumbers(_ numbers: [Int]) -> [Int] {

var squares: [Int] = []

for number in numbers {

squares.append(number * number)

}

return squares

}

let numbers = [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 ]

squareNumbers(numbers)And doing the same thing using map:

func squareNumbersUsingMap(_ numbers: [Int]) -> [Int] {

let squares = numbers.map { $0 * $0 }

return squares

}In this case, the type of the data did not change: integers went in, integers came out.

But map can change the type as well.

func squareRoots(_ numbers: [Int]) -> [Double] {

let roots = numbers.map { number in

sqrt(Double(number))

}

return roots

}

squareRoots(numbers)And there is a final twist to map that used to be called flatMap but is now called compactMap and that allows us to get rid of optionals as we map through an array.

func convertStringsToInts(_ strings: [String]) -> [Int] {

let ints = strings.compactMap { return Int($0) }

return ints

}

let strings = [ "1", "two", "", "0.34", "65", "-93", "4e8" ]

convertStringsToInts(strings)The conversion of String to Int may fail and so returns an optional. If this function had used map instead of compactMap, the result would have been an array of optional Ints: [Int?]. By using compactMap, every nil value was dropped and only valid integers are included.

Reduce

The final tool in the immutability toolbox is reduce and this is one that took me a while to wrap my head around.

Imagine that you wanted to add up all the integers in an array. Here is a way to do it using a mutable variable and a loop:

func sumNumbers(_ numbers: [Int]) -> Int {

var total = 0

for num in numbers {

total += num

}

return total

}

let numbers = [ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 ]

sumNumbers(numbers)I can't use filter or map here because I want to end up with a single value after applying some logic to every item in the array. So here is where I use reduce.

func sumNumbersUsingReduce(_ numbers: [Int]) -> Int {

let total = numbers.reduce(0) { (cumulativeTotal, nextValue) in

return cumulativeTotal + nextValue

}

return total

}

sumNumbersUsingReduce(numbers)The reduce function takes 2 parameters. The first is the starting value - in this case it is zero. The second paramter is a function (I am using a closure) this in turn takes 2 parameters and here is where it gets complicated. Inside the closure function, the 2 parameters are the current result and the next value from the loop. And what you return from this closure is going to be the new cumulative value which will either be fed back into the loop, or returned as the final result. The first time through the loop, the first parameter will be the initial value as set in the reduce function call.

To see how this happens, here is a version sprinkled with print statements showing what happens each time through the loop:

func sumNumbersReduceDebug(_ numbers: [Int]) -> Int {

let total = numbers.reduce(0) { (cumulativeTotal, nextValue) in

print("cumulativeTotal = \(cumulativeTotal)")

print("nextValue = \(nextValue)")

print("about to return \(cumulativeTotal) + \(nextValue) = \(cumulativeTotal + nextValue) which will become the next culmulative or the final value")

return cumulativeTotal + nextValue

}

print("final result = \(total)")

return total

}

let shortNumbers = [ 5, 3, 8 ]

sumNumbersReduceDebug(shortNumbers)This produces a log showing:

cumulativeTotal = 0

nextValue = 5

about to return 0 + 5 = 5 which will become the next culmulative or the final value

cumulativeTotal = 5

nextValue = 3

about to return 5 + 3 = 8 which will become the next culmulative or the final value

cumulativeTotal = 8

nextValue = 8

about to return 8 + 8 = 16 which will become the next culmulative or the final value

final result = 16Using functions as building blocks

This one is more a matter of style than of any particular programming technique. Basically, keep each function small and break your code into small chunks with obvious naming. This makes your code easier to read, test and debug and it beomes vastly more reusable.

Consider this totally made-up function:

func configureDisplay(for userId: String?) {

guard let userId = userId else {

showLoginScreen()

return

}

displayUserData(for: userId)

let userType = getPermissions(for: userId)

populateMenus(for: userType)

loadInitialData(for: userId)

playSound(.welcome)

}

configureDisplay(for: "abc123")

configureDisplay(for: nil)Is it easy to read? Can you work out what it does? Now imagine all that functionality in a single huge function - would that be as good to use?

As a way of encouraging shorter functions, which leads inevitably to this sort of structured code, I strongly recommend using SwiftLint to check your code. I wrote a post about this a while ago which you might find useful.

Naming

The other key thing to mention and it is a point that Apple makes very strongly, is to name your functions and their parameters so as to make them as readable as possible from the calling site. You write a function once, but you most likely call it multiple times, so it is the calling site that needs to be really easy to read.

Returning to the game example, here is a dummy function to show damage caused to a target:

func displayDamage(damage: Int, target: String) {}

displayDamage(damage: 31, target: "Ogre")There is nothing really wrong with the function, but calling it is a bit clunky and doesn't read well with the repeated use of the word 'damage'.

What about this version?

func display(damage: Int, doneTo target: String) {}

display(damage: 42, doneTo: "Wolf")There are no repeated words in the caller and by using two labels for the second parameter, the calling site can read almost like a sentence, but inside the function, target is still a more logical name.

A third alternative is to use an un-named parameter if the naming logic is implicit in the function name itself:

func displayDamage(_ damage: Int, doneTo target: String) {}

displayDamage(12, doneTo: "Orc")Closures

As promised above, a very quick explanation of closures, which really deserve their own post...

In Swift, as in many languages, functions can be passed as parameters to other functions. As an example, I have set up 2 functions to perform a simple calculation on a given integer:

func cube(_ number: Int) -> Int {

return number * number * number

}

cube(3)

func square(_ number: Int) -> Int {

return number * number

}

square(3)Now imagine that you wanted to create a more general function that could call either one of these functions with any number:

func doCalculation(_ number: Int, calculation: (Int) -> Int) -> Int {

return calculation(number)

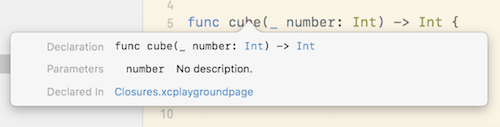

}doCalculation takes 2 parameters. The first one is easy - it is just an integer. The second one is weird! For every parameter of a function, you have to supply the type of that parameter. Usually this is quite straight-forward: Int, String, MyCustomClass etc. But what is the type of a function? Option-clicking on the word cube in my function definition, I see this:

And ignoring the parameter labels, this basically provides the function type: Int inside parentheses for the input, then the arrow, then Int again for the return type. So the type definition for the cube function is (Int) -> Int. And when I define the type for the calculation parameter in the doCalculation function, this is exactly what I put. The last part of the function definition is specifiying the overall return type as an Int.

Using the cube and square functions inside doCalculation works like this:

doCalculation(7, calculation: square)

doCalculation(4, calculation: cube)But what if I didn't want to define all the functions I might call in advance? Then I can send the function body to the doCalculation function instead of using a pre-built function. This way of using a function inside another function is referred to as a closure.

doCalculation(6, calculation: { number in

return number * 12

})The doCalculation function in unchanged, but instead of passing it a reference to a function, I am directly passing it the instructions it should use to get the result. As with any function, the instructions are contained within a set of curly braces. The input to this function is listed after the opening curly brace followed by the keyword in. Then the function body does whatever it needs to and returns the result.

You may have heard the term trailing closure. This refers to a function where the last parameter is a function. If that function is called using a closure, there is a short-hand way of writing this, omitting the closure's parameter name and moving the closing parenthesis to before the opening curly brace.

doCalculation(16) { number in

return number % 3

}With the filter, map and reduce functions I showed above, this is the way their logic was supplied but here is how the filter example would look without using a closure:

func checkName(_ name: String) -> Bool {

return name.count > 3 && !name.contains(" ")

}

func checkPlayerNamesUsingFunction(names: [String]) -> [String] {

let validNames = names.filter(checkName)

return validNames

}

let allNames = [ "Woody", "Rex", "Slinky", "Buzz Lightyear", "Hamm" ]

let checkedNames = checkPlayerNamesUsingFunction(names: allNames)Which methods you use are up to you - they all work. If you have a function that will be called in many different places, maybe it makes more sense to define it once and pass around a reference to that function. If not, a closure has the advantage that it keeps everything together. There is more to closures, particularly to do with variable scope, but I think this post has gone on long enough already.... maybe next time.